Table of Contents

Definition of Building Foundation

Foundations transfer forces from structural systems to some external source, typically the ground. The ground has essentially infinite stability, which makes it a great place to transfer the loads of your structure.

In a structural model, foundations are often represented as Supports, or boundary conditions. They act as an endpoint for a load path.

Foundations serve several purposes, including:

- In the short term, stabilize and support the structure.

- In the long term, resist differential settlement and increase the lifespan of the structure.

- Distribute loads from columns to a larger area.

- Redistribute uneven structural loads.

- Protect the structure against soil erosion underneath the foundation.

- Assist in lateral stability against lateral loads such as wind and earthquakes.

The soil where the foundation sits, or is piled into, is a critical aspect of a foundation’s design and must be analyzed and checked for its stability. Different soil types such as clay behave very differently to others such as sand. These behavioural differences are expressed through physical values such as soil cohesion and friction angle.

Types of Foundations

Generally, foundation systems are divided into shallow and deep foundations. Shallow foundations are almost always cast against the earth. The site is excavated to relatively shallow depths, underneath the ground elevation. They are easier to construct, cheaper, and, therefore, usually a more popular design option for smaller structures.

Figure 1: Foundation Systems

Difference Between ‘Footings’ and ‘Foundations’

The terms footing and foundation are commonly confused for one another.

A ‘foundation’ is a general term used to denote a part of a structure that transfers the load from the superstructure to the supporting ground. It can be either classified as a shallow or deep foundation.

A ‘footing’ is a part of a foundation in contact with the ground. Typically, footings are associated with shallow foundations only. Refer to the Foundation Systems diagram above. All footings are considered foundations, but not all foundations are footings.

Difference between Deep and Shallow Foundations

Shallow foundations are used primarily when the load will be transferred into a bearing soil located at a shallow depth (as little as 1 meter or 3 feet). Deep foundations are used when the load is transferred into deep strata (ranging from 20-65 meters or 60-200 feet).

Deep foundations are more commonly found on sites where the soil conditions are unfavorable. For example, most marine projects will use deep foundations for additional stability. The process of constructing a deep foundation is more complex and costly. It requires heavier equipment, skilled labor, and proper time management. Deep foundations can be driven into the ground or cast against the earth, soil is much harder to excavate, and soil pressure increases as you go deeper. A deep foundation provides lateral support, resists uplift, and supports larger loads. It relies on both end bearing and skin friction.

By comparison, shallow foundations are cheaper, requiring less labor, equipment, and materials. They rely primarily on end bearing on the soil. Reinforcement in shallow foundations helps resist overturning and bending of the foundation.

Shallow Foundations

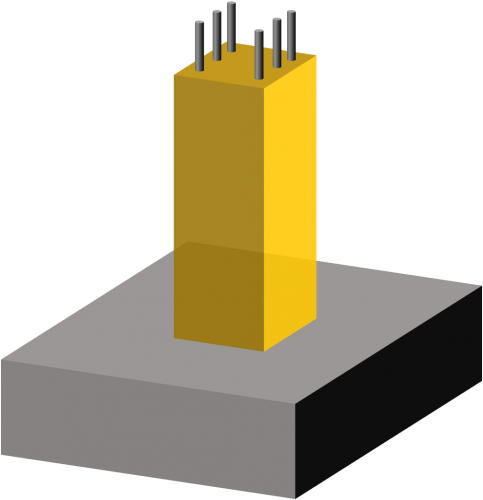

Isolated Footings

Isolated footings, also known as spread or pad footings, are the simplest and most common type of foundation. Each footing supports its column that it takes the load from and spreads it to the soil it’s bearing on. Isolated footings are almost always square or rectangular. This makes them easier to analyze and construct. Dimensions of the footing are estimated based on the loads from the column, the safe bearing capacity, and excessive soil settlement.

Figure 2: Isolated Footing

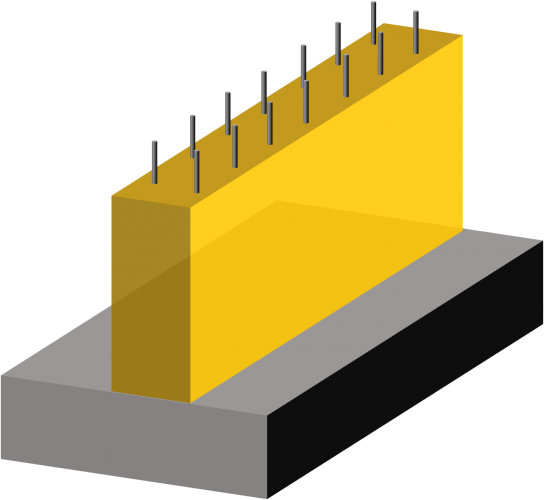

Wall Footings

Wall footings, also known as strip footings, support the weight from load-bearing and non-structural walls. Similar to isolated footings, the greater the footing area, the greater the ability for the footing to limit settlement. Strip footings are useful in supporting load-bearing walls, as they resist not just dead loads of the structure, but also other design loads. Wall footings are also cast with plain or reinforced concrete and sometimes are precast before being brought to the site.

Figure 3: Wall Footing

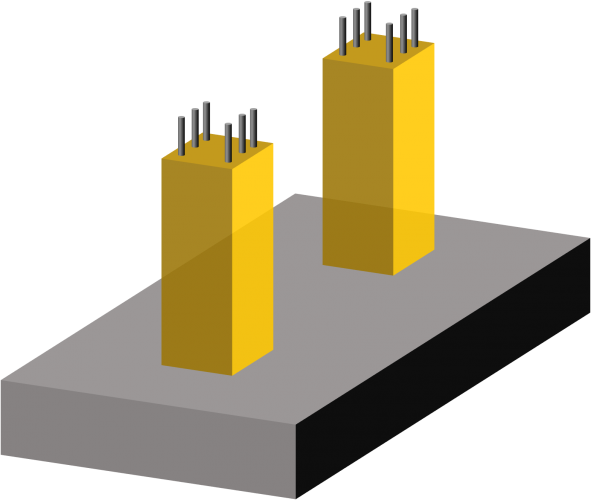

Combined Footings

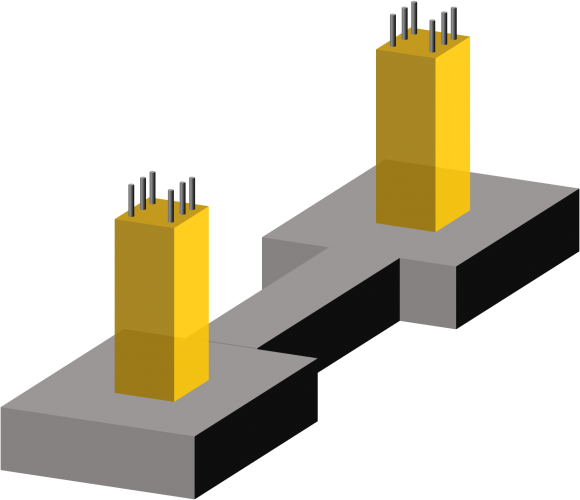

Like isolated footings, the combined footing is constructed when columns carry structural loads. This is used when two or more columns are so close to each other that their isolated footing overlap. Construction of combined footings may be more economical when the footing materials (concrete) are cheaper than the labor to form two separate footings. Combined footings may be rectangular, trapezoidal, or tee-shaped, depending on the size and location of the columns supported by the footing.

Figure 4: Combined Footing

Strap Footings

Strap footings, also known as cantilever footings, are two isolated footings connected with a strap beam.

Strap beams commonly connect two footings that support columns resisting significant lateral forces. The central strap beam will help reduce the effects of the lateral load without placing additional gravity pressure onto the soil, which would occur if a combined footing were used.

Figure 5: Strap Foundation

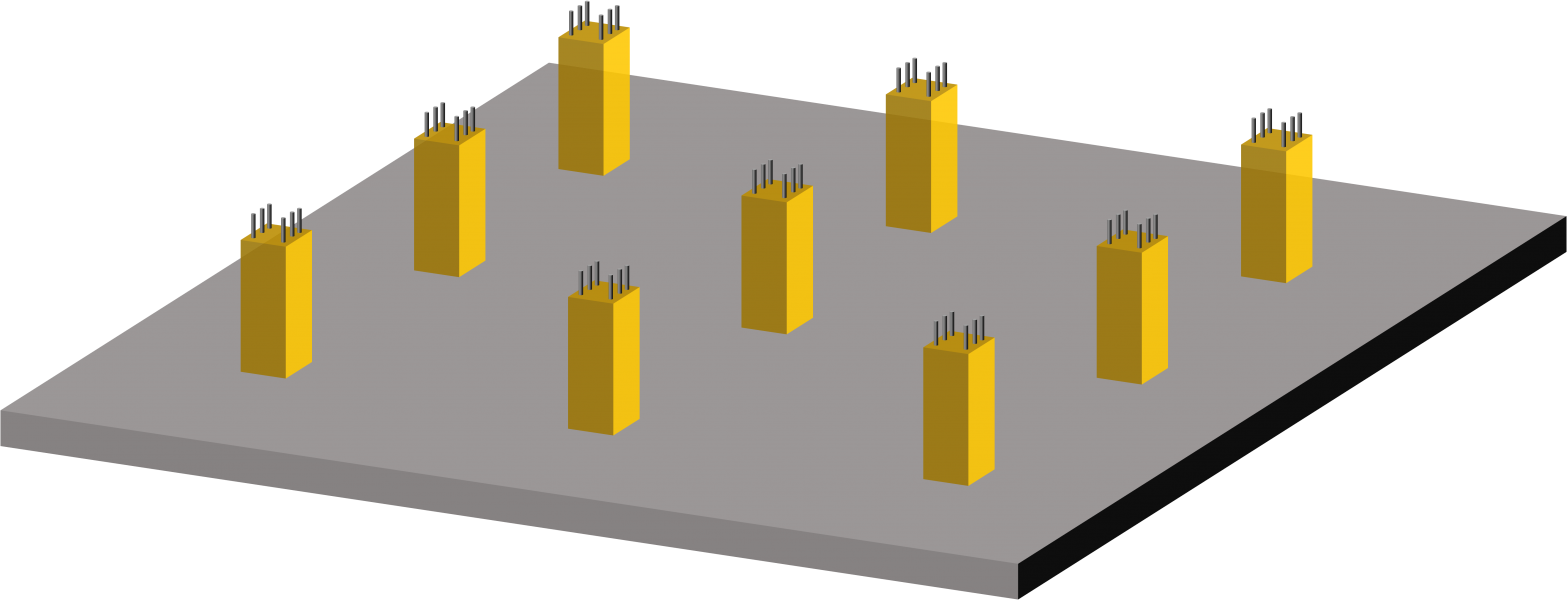

Mat Foundation

As the name implies, a mat foundation, also known as raft foundation, is a type of foundation spread entirely across the area of the building supporting heavy loads from columns or walls, similar to a slab on ground. It is most often used with basement construction where the entire basement floor slab acts as the foundation. Mat foundation is chosen when the building is supported by weak soil. Thus building loads are spread over an extremely large area. This prevents differential settlement that would be prevalent with isolated footings. This is most suitable and economical to use when the building footprint is relatively small or if columns are close together, limiting material cost. Conversely, mat foundations are not desirable to construct when the groundwater is located above the bearing surface of the soil.

Figure 6: Mat or Raft Foundation

Deep Foundations

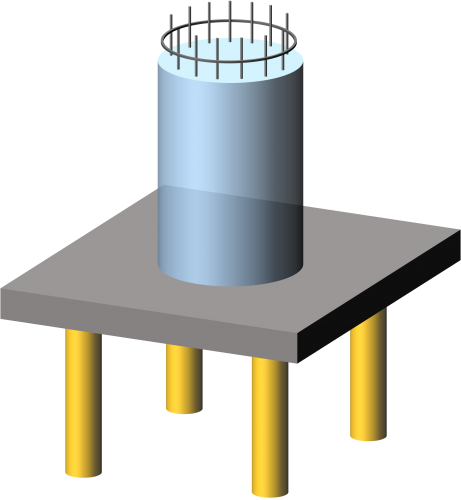

Pile Foundation

Advantages of using pile foundations:

- Piles can be precast into any required specification or design requirement in a controlled environment.

- Precast piles are shipped to the site and immediately able for installation, thus resulting in more rapid work progress.

- Cast-in-place concrete piles can support large and tall structures like skyscrapers, where a shallow foundation would not suffice.

- Driven piles can also be used in locations where it is not advisable to drill holes due to pressurized groundwater tables.

- Pile foundations can be used in locations where soil conditions make other foundation types impossible.

Disadvantages of using pile foundations:

- Concrete piles need to be reinforced adequately to sustain the stresses if driven into the ground

- Planning and equipment is essential for proper handling and driving of piles into the ground

- The heaving of the soil or an already driven pile may pop up when a pile is driven into the soil with low or poor drainage qualities.

- The driving of piles generates vibration, affecting the integrity of adjacent structures.

Figure 7: Pile Foundations and Pile Cap

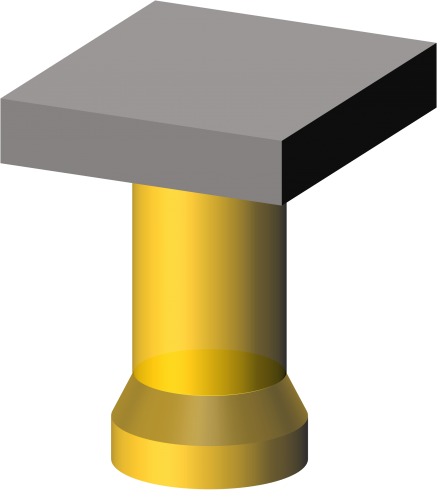

Pier (Caisson) Foundation

Pier or Caisson foundations are similar to a single pile foundation but with a larger “pile” column diameter. Caisson foundations are also installed differently. Unlike the pile foundation, pier foundations are constructed by excavating or dredging the soil beneath the ground and filling it with concrete and steel reinforcement. Caissons can also be drilled into the bedrock or rest on soil strata, but a “belled” cross-section is required to spread the load over a wider area (as shown in Figure 8). Because of the presence of water, pier foundations rely on end bearing to resist the superstructure loads, contrary to the pile foundation, which transfers loads through end bearing and skin friction. Typically, pile foundations are installed when there are no firm strata at a reachable depth, and pier foundations are often used when the top layer of soil consists of decomposed rocks or stiff clay.

Figure 8: Pier or Caisson Foundation with Pile Cap

Free Concrete Footing Calculator

I hope this tutorial has helped you understand more about different types of foundation used in structural engineering. Check out our Free Concrete Footing Calculator, a simplified version of SkyCiv Foundation Design Software, or sign up today to get started with SkyCiv software!